Labour Force Survey, May 2017

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please "contact us" to request a format other than those available.

Released: 2017-06-09

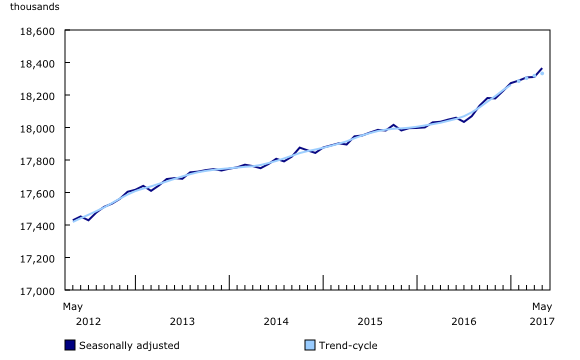

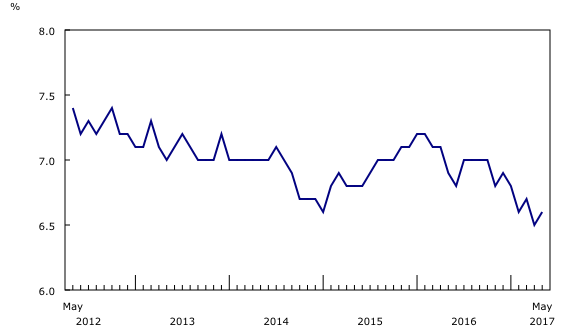

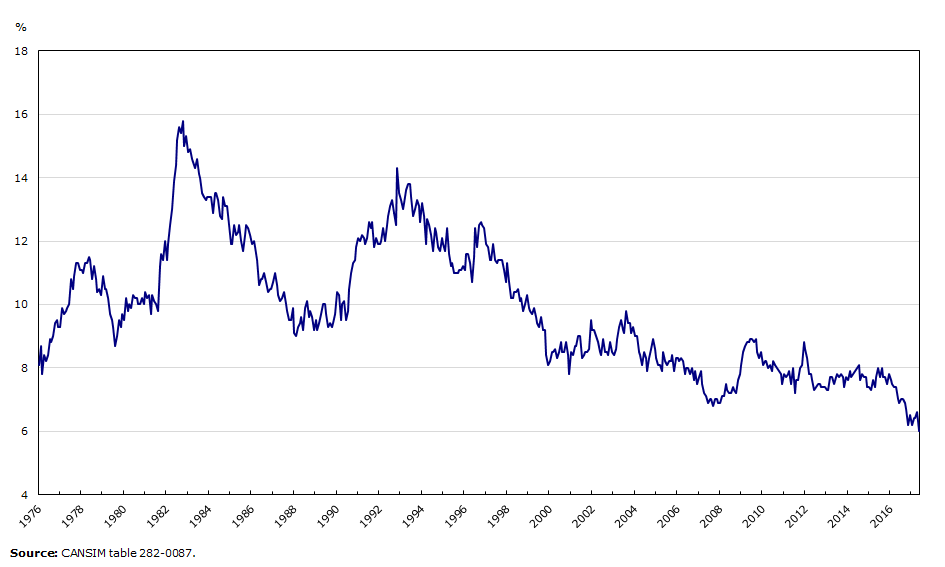

Employment rose by 55,000 in May, spurred by an increase in full-time work (+77,000). At the same time, the unemployment rate rose by 0.1 percentage points to 6.6%, the result of more people participating in the labour market. The employment increase in May builds on gains since July 2016, when the current upward trend began.

Compared with 12 months earlier, there were 317,000 (+1.8%) more people employed, mostly the result of increases in full-time work. Over the same period, the total number of hours worked rose 0.7%.

Highlights

In May, employment increased among youth aged 15 to 24 and men aged 25 to 54. At the same time, employment held steady for women aged 25 to 54 and people 55 years of age and older.

Employment rose in Ontario, British Columbia, Manitoba and Prince Edward Island. There was little change in the other provinces.

In May, employment increased in several industries, led by professional, scientific and technical services as well as manufacturing. There were smaller increases in transportation and warehousing; wholesale and retail trade; as well as health care and social assistance. In contrast, fewer people worked in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing; information, culture and recreation; and public administration.

The number of private sector employees increased in May, while public sector employment and self-employment were little changed.

Employment up for youth and men aged 25 to 54

In May, employment among youth aged 15 to 24 rose by 28,000, the result of full-time gains, largely in Ontario and British Columbia. This was the first notable increase for youth since October 2016. The youth unemployment rate was little changed in May at 12.0%, as more young people participated in the labour market. Compared with 12 months earlier, youth employment increased by 2.7% (+64,000), the fastest year-over-year growth since February 2013. This year-over-year gain was mostly in part-time work. Over the same 12-month period, the youth population declined by 0.9% (-38,000), continuing a downward trend.

Employment for men aged 25 to 54 rose by 25,000 in May, the third notable monthly increase so far in 2017. The unemployment rate for men in this age group fell by 0.3 percentage points to 5.8%. On a year-over-year basis, employment for men aged 25 to 54 rose by 96,000 (+1.5%), with increases evenly distributed between full- and part-time work.

For women aged 25 to 54, employment held steady in May and their unemployment rate was 5.3%. In the 12 months to May, employment for this group of women rose by 61,000 (+1.1%), the result of gains in full-time work.

Among people aged 55 and older, employment was little changed in May, while their unemployment rate rose by 0.4 percentage points to 6.0% as more people in this age group searched for work. On a year-over-year basis, more people aged 55 and older were working (+96,000 or +2.6%), largely the result of the continued transition of the baby-boom cohort into this older age group.

Notable employment gains in four provinces

In Ontario, employment increased by 20,000 in May, the result of additional employment among youth aged 15 to 24. The overall unemployment rate in Ontario rose by 0.7 percentage points to 6.5% as more people searched for work. Compared with 12 months earlier, employment in Ontario was up 86,000 (+1.2%).

In British Columbia, employment increased by 12,000 in May, continuing an upward trend that began in the spring of 2015. Compared with May 2016, employment in the province grew by 99,000 (+4.2%), mostly the result of gains in full-time work. The unemployment rate in British Columbia was little changed at 5.6% in May.

Employment in Manitoba rose by 2,700 in May, bringing total gains since November 2016 to 11,000 (+1.7%). In May, the unemployment rate in the province was little changed at 5.3%.

There were an estimated 1,500 more people working in Prince Edward Island in May, and the unemployment rate for the province was little changed at 10.0%. Prince Edward Island has had relatively strong employment growth since the autumn of 2016. On a year-over-year basis, employment in the province was up 3,400 (+4.7%).

In Quebec, employment edged up 15,000 in May as a notable gain in full-time work was partly offset by a slight decline in part-time employment. With fewer job-seekers, Quebec's unemployment rate fell 0.6 percentage points to a record low 6.0%, continuing a downward trend since the beginning of 2016. In the 12 months to May, employment in the province increased by 83,000 (+2.0%), mostly in the second half of 2016.

Employment in Alberta held steady in May as full-time gains totalling 19,000 were offset by losses in part-time work. Employment in the province increased by 41,000 (+1.8%) on a year-over-year basis.

Widespread industry employment gains

In May, employment increased by 26,000 in professional, scientific and technical services, contributing to year-over-year gains totalling 50,000 (+3.6%). Ontario and Quebec accounted for the bulk of the increase in May.

Following a downward trend in manufacturing throughout 2016, employment rose by 25,000 in May, the second increase in three months. Ontario had the largest gain in the month. Since the start of 2017, gains in manufacturing have totalled 43,000 (+2.6%).

There were 17,000 additional workers in transportation and warehousing in May, continuing an upward trend that began at the start of 2016. The increase in May was mainly in Quebec. On a year-over-year basis, national employment in this industry increased by 40,000 (+4.4%).

In wholesale and retail trade, employment increased for the third time in four months, up 15,000 in May, powered by gains in Ontario. On a year-over-year basis, there were 74,000 (+2.7%) more people employed in the industry. Wholesale and retail trade continued to be the largest industry group by employment, accounting for an estimated 2.8 million people or 15.3% of all workers.

Employment in health care and social assistance increased for the second consecutive month, up 15,000 in May. The lion's share of the increase was in Ontario. The added employment in May boosted total gains at the national level for the industry to 63,000 (+2.7%) from May 2016.

Employment declined by 17,000 in finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing, the first notable decrease since November 2015. Ontario accounted for all of the decline in May. Despite fewer workers in May, employment in the industry was up 38,000 (+3.4%) compared with May 2016.

Information, culture and recreation employment declined by 16,000 in May, contributing to losses totalling 28,000 since the start of 2017. The decline in May was mainly in Ontario. As a result of these recent declines, employment in the industry matched the level observed in May 2016.

There were 12,000 fewer people working in public administration in May, with declines in Ontario and British Columbia. Despite the decline in the month, employment in the industry increased by 26,000 (+2.8%) in the 12 months to May, with gains in local, municipal and regional public administration as well as federal public administration.

The number of private sector employees increased by 59,000 in May, while there was little change in public sector employment. On a year-over-year basis, the number of private sector employees rose by 213,000 (+1.8%) and public sector employment was up 77,000 (+2.1%).

Self-employment was little changed both in the month and compared with May 2016.

Summer employment for students

From May to August, the Labour Force Survey collects labour market data on youths aged 15 to 24 who were attending school full time in March and who intend to return to school full time in the fall. The May survey results provide the first indicators of the summer job market, especially for students aged 20 to 24, as many younger students are still in school. Data for June, July and August will provide further insight into the summer job market. Published data are not seasonally adjusted and, therefore, comparisons can only be made with data for the same month in previous years.

In May, employment among 20- to 24-year-old students was virtually unchanged and the employment rate was 58.9%, little changed from 12 months earlier. The unemployment rate for this group of students was 13.3%, also little changed compared with May 2016.

In May, there were 19,000 additional 17- to 19-year-old students employed compared with May2016, resulting in a slight increase in their employment rate, up 1.3 percentage point to 51.4%. All of the employment increase for this group of students was in part-time work. The unemployment rate for this younger group of students was 14.7%.

Canada–United States comparison

Adjusted to the concepts used in the United States, the unemployment rate in Canada was 5.6% in May, compared with 4.3% in the United States. In the 12 months to May 2017, the unemployment rate fell by 0.3 percentage points in Canada and by 0.4 percentage points in the Unites States.

The labour force participation rate in Canada (adjusted to US concepts) was 65.7% in May compared with 62.7% in the United States. On a year-over-year basis, the participation rate increased by 0.2 percentage points in Canada, while it edged up by 0.1 percentage points in the United States.

The US-adjusted employment rate in Canada stood at 62.1% in May compared with 60.0% in the United States. On a year-over-year basis, the employment rate rose by 0.5 percentage points in Canada and by 0.3 percentage points in the United States.

For further information on Canada–US comparisons, see "Measuring Employment and Unemployment in Canada and the United States – A comparison."

In celebration of the country's 150th birthday, Statistics Canada is presenting snapshots from our rich statistical history.

Evolution of self-employment

Self-employment has evolved over the last 70 years, accounting for a smaller share of total employment in 2016 compared with earlier in the 20th century. Several factors are associated with changes in self-employment; such as periods of economic downturns, changes in the composition of employment by industry, as well as changes in type of contract work, and technological changes.

In 1946, one-third (33%) of all workers in Canada were self-employed. At that time, agriculture workers accounted for the majority of self-employment (68%).

Due in large part to the declining prevalence of agricultural employment, self-employment fell in subsequent decades. By 1976, self-employed workers accounted for 12% of the Canadian workforce, increasing to 14% in 1986 and 16% in 1996. Over the past 20 years, this share has hovered around 15% to 16%.

In 2016, self-employment was found in a variety of industries, led by professional, scientific and technical services (16%); construction (15%); and health care and social assistance (11%). In 2016, agriculture accounted for 6% of self-employment.

For further information on self-employment, see "Self-employment in the downturn," Perspectives on Labour and Income (75-001-X) and "The Performance of the 1990s Canadian Labour Market," in Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series (11F0019M).

Note to readers

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) estimates for May are for the week of May 14 to 20.

The LFS estimates are based on a sample and are therefore subject to sampling variability. As a result, monthly estimates will show more variability than trends observed over longer time periods. For more information, see "Interpreting Monthly Changes in Employment from the Labour Force Survey." Estimates for smaller geographic areas or industries also have more variability. For an explanation of the sampling variability of estimates and how to use standard errors to assess this variability, consult the "Data quality" section of the publication Labour Force Information (71-001-X).

This analysis focuses on differences between estimates that are statistically significant at the 68% confidence level.

The LFS estimates are the first in a series of labour market indicators released by Statistics Canada, which includes indicators from programs such as the Survey of Employment, Payrolls and Hours (SEPH), Employment Insurance Statistics, and the Job Vacancy and Wage Survey. For more information on the conceptual differences between employment measures from the LFS and SEPH, refer to section 8 of the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The employment rate is the number of employed people as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate for a particular group (for example, youths aged 15 to 24) is the number employed in that group as a percentage of the population for that group.

The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed as a percentage of the labour force (employed and unemployed).

The participation rate is the number of employed and unemployed as a percentage of the population.

Full-time employment consists of persons who usually work 30 hours or more per week at their main or only job.

Part-time employment consists of persons who usually work less than 30 hours per week at their main or only job.

Seasonal adjustment

Unless otherwise stated, this release presents seasonally adjusted estimates, which facilitate comparisons by removing the effects of seasonal variations. For more information on seasonal adjustment, see Seasonally adjusted data – Frequently asked questions.

Chart 1 shows trend-cycle data on employment. These data represent a smoothed version of the seasonally adjusted time series, which provides information on longer-term movements, including changes in direction underlying the series. These data are available in CANSIM table 282-0087 for the national level employment series. For more information, see the StatCan Blog and Trend-cycle estimates – Frequently asked questions.

Next release

The next release of the LFS will be on July 7.

Products

A more detailed summary, Labour Force Information (71-001-X), is now available for the week ending May 20.

More information about the concepts and use of the Labour Force Survey is available online in the Guide to the Labour Force Survey (71-543-G).

The updated Labour Market Indicators dashboard (71-607-X) is now available. This new, interactive dashboard provides easy, customizable access to key labour market indicators. Users can now configure an interactive map and chart showing labour force characteristics at the national, provincial or census metropolitan area level.

Contact information

For more information, or to enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact us (toll-free 1-800-263-1136; 514-283-8300; STATCAN.infostats-infostats.STATCAN@canada.ca) or Media Relations (613-951-4636; STATCAN.mediahotline-ligneinfomedias.STATCAN@canada.ca).

To enquire about the concepts, methods or data quality of this release, contact Andrew Fields (613-951-3551; andrew.fields@canada.ca), Vincent Ferrao (613-951-4750; vincent.ferrao@canada.ca) or Client Services (toll-free 1-866-873-8788; statcan.labour-travail.statcan@canada.ca), Labour Statistics Division.

- Date modified: