Information for respondents

Additional information

Your information may also be used by Statistics Canada for other statistical and research purposes.

Your participation in this survey is required under the authority of the Statistics Act.

Authority

Data are collected under the authority of the Statistics Act, Revised Statutes of Canada, 1985, Chapter S-19.

Confidentiality

By law, Statistics Canada is prohibited from releasing any information it collects that could identify any person, business, or organization, unless consent has been given by the respondent, or as permitted by the Statistics Act. Statistics Canada will use the information from this survey for statistical purposes only.

Data-sharing agreements

To reduce respondent burden, Statistics Canada has entered into data-sharing agreements with provincial and territorial statistical agencies and other government organizations, which have agreed to keep the data confidential and use them only for statistical purposes. Statistics Canada will only share data from this survey with those organizations that have demonstrated a requirement to use the data.

Section 11 of the Statistics Act provides for the sharing of information with provincial and territorial statistical agencies that meet certain conditions. These agencies must have the legislative authority to collect the same information, on a mandatory basis, and the legislation must provide substantially the same provisions for confidentiality and penalties for disclosure of confidential information as the Statistics Act. Because these agencies have the legal authority to compel businesses to provide the same information, consent is not requested and businesses may not object to the sharing of the data.

For this survey, there are Section 11 agreements with the provincial and territorial statistical agencies of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia and the Yukon.

The shared data will be limited to information pertaining to business establishments located within the jurisdiction of the respective province or territory.

Section 12 of the Statistics Act provides for the sharing of information with federal, provincial or territorial government organizations. Under Section 12, you may refuse to share your information with any of these organizations by writing a letter of objection to the Chief Statistician, specifying the organizations with which you do not want Statistics Canada to share your data and mailing it to the following address:

Chief Statistician of Canada

Statistics Canada

Attention of Director, Investment, Science and Technology Division

150 Tunney's Pasture Driveway

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0T6

You may also contact us by email at statcan.istdinformation-distinformation.statcan@statcan.gc.ca.

For this survey, there are Section 12 agreements with the statistical agencies of Prince Edward Island, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, as well as with Public Safety Canada .

For agreements with provincial and territorial government organizations, the shared data will be limited to information pertaining to business establishments located within the jurisdiction of the respective province or territory.

Record linkage

To enhance the data from this survey and to reduce respondent burden, Statistics Canada may combine it with information from other surveys or from administrative sources.

Reporting instructions

For this questionnaire:

Please complete this questionnaire for Canadian operations of this organization.

- Report dollar amounts in Canadian dollars.

- Report dollar amounts rounded to the nearest dollar.

- If precise figures are not available, provide your best estimate.

- Enter "0" if there is no value to report.

Organization characteristics

Organization characteristics - Question identifier: 1

Which of the following does your organization currently use? Select all that apply.

- Website for your organization

- Social media accounts for your organization

- E-commerce platforms and solutions

- Web-based applications

- Open source software

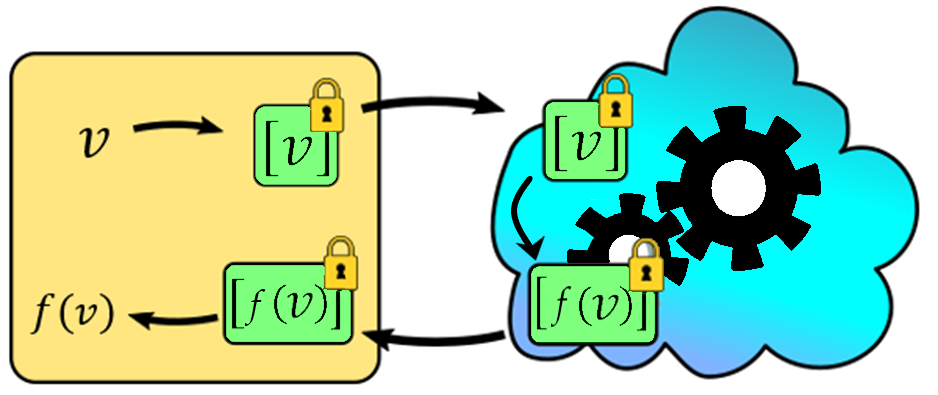

- Cloud computing or storage

- Internet-connected smart devices or Internet of Things (IoT)

- Intranet

- Blockchain technologies

- Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services

- OR

- Organization does not use any of the above

Organization characteristics - Question identifier: 2

What type of data does your organization store on cloud computing or storage services? Include data that are backed-up. Select all that apply.

- Confidential employee information

- Confidential information about customers, suppliers or partners

- Confidential organizational information

- Commercially sensitive information

- Non-sensitive or public information

- OR

- Organization does not store data on cloud computing or storage services

Organization characteristics - Question identifier: 3

Does anyone in your organization use personally-owned devices such as smartphones, tablets, laptops or desktop computers to carry out regular work-related activities? Include devices that are subsidized by the organization.

Cyber security environment

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 4

Which cyber security measures does your organization currently have in place?

Include on-site and external security measures, including those provided by parent organizations or other external parties (e.g., Shared Services Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat). Select all that apply.

- Mobile security

- Anti-malware software to protect against viruses, spyware, ransomware, etc.

- Web security

- Email security

- Network security

- Data protection and control

- Point-Of-Sale (POS) security

- Software and application security

- Hardware and asset management

- Identity and access management

- Physical access controls

- OR

- Organization does not have any cyber security measures in place

- OR

- Do not know

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 5

Did any of the following parent organizations or external parties require your business or organization to implement certain cyber security measures?

Select all that apply.

- Supplier of physical goods

- Supplier of digitally delivered goods or services

- Supplier of other services that are not digitally delivered

- Customer

- Partner

- Canadian regulator

- Cyber security standard or cyber security certification program

- Federal Government lead agency, partner or service provider

- Cyber risk insurance provider

- OR

- None of the above

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 6

How many employees does your organization have that complete tasks related to cyber security as part of their regular responsibilities?

Include part-time and full-time employees. Examples of tasks these employees may complete include:

- managing, evaluating or improving the security of networks, web presence, email systems or devices

- patching or updating the software or operating systems used for security reasons

- completing tasks related to recovery from previous cyber security incidents.

Exclude individuals employed by a parent organization, or external IT consultants or contractors.

If precise figures are not available, please provide your best estimate.

- One employee

- Two to five employees

- 6 to 15 employees

- Over 15 employees

- None

- Do not know

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 7

What are the main reasons your organization does not have any employees that complete tasks related to cyber security as part of their regular responsibilities? Select all that apply.

- Organization uses private sector consultants or contractors to monitor cyber security

- Organization uses public sector consultants or contractors to monitor cyber security

- Organization has cyber risk insurance

- Organization is in the process of recruiting a cyber security employee

- Organization is unable to find an adequate cyber security employee

- Organization lacks the resources to employ a cyber security employee

- Cyber security is not a high enough risk to the organization

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 8

What percentage of the employees that complete tasks related to the cyber security of your organization as part of their regular responsibilities identify as the following genders? Gender refers to current gender, which may be different from sex assigned at birth and may be different from what is indicated on legal documents.

Exclude individuals employed by a parent organization, or external IT consultants or contractors.

If precise figures are not available, please provide your best estimate.

- Female

- Male

- Another gender

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 9

Did your organization share best practices or general information on cyber security risks with your employees in 2022?

Include the sharing of information through email, bulletin boards, general information sessions on subjects related to:

- recognizing and avoiding email scams

- importance of password complexity and basic security techniques

- securing your web browser and safe web browsing practices

- avoiding phishing attacks

- recognizing and avoiding spyware.

- Information shared with internal IT personal

- Information shared with other employees

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

- Do not know

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 10

Did your organization provide formal training to develop or upgrade cyber security related skills of your employees or stakeholders in 2022 ? Include training provided by parent organizations or other external sources.

- Provided training to internal IT personnel

- Provided training to other employees

- Provided training to stakeholders such as suppliers, customers or partners

- Yes

- No

- Not applicable

- Do not know

Cyber security environment - Question identifier: 11

What are the three main reasons your organization spends time or allocates budget on cyber security measures or related skills training? Select up to three.

- Allow employees to work remotely securely

- Protect the reputation of the organization

- Protect personal information of employees, suppliers, customers or partners

- Protect trade secrets and intellectual property

- Compliance with laws, regulations, contracts or other government organizations

- Organization has suffered a cyber security incident previously

- Prevent downtime and outages

- Prevent fraud and theft

- Secure continuity of organizational operations

- OR

- Organization does not spend time or money on cyber security measures or related skills training

Cyber security readiness

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 12

Which risk management arrangements does your organization currently have in place?

Select all that apply.

- A written policy in place to manage internal cyber security risks

- A written policy in place to manage cyber security risks associated with supply chain partners

- A written policy in place to report cyber security incidents

- Other type of written policy related to cyber security

- A Business Continuity Plan (BCP) with processes to manage cyber security threats, vulnerabilities and risks

- Employees with responsibility for overseeing cyber security risks and threats

- Members of senior management with responsibility for overseeing cyber security risks and threats

- A consultant or contractor to manage cyber security risks and threats

- Monthly or more frequent patching or updating of operating systems for security reasons

- Monthly or more frequent patching or updating of software for security reasons

- Cyber risk insurance

- OR

- Organization does not have any risk management arrangements for cyber security

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 13

Which are covered under your cyber risk insurance policy? Select all that apply.

- Direct losses from an incident

- Restoration expenses for software, hardware, and electronic data

- Interruptions (loss of productive time) and reputation losses

- Third-party liability

- Financial losses

- Security breach remediation and notification expenses

- Claims made by employees

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 14

Prior to responding to this survey, were you aware of any cyber security standards or cyber security certification programs that organizations can apply for?

Include:

- Canadian, foreign and international standards and programs

- standards and programs that you were aware of but your organization was not eligible for or did not apply for.

Select all that apply.

- Cyber security standards

- Specify which standards you were aware of

- Cyber security certification programs

- Specify which certification programs you were aware of

- OR

- Not aware of any cyber security standards or certification programs

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 15

Which activities does your organization undertake to identify cyber security risks?

Select all that apply.

- Monitoring employee behaviour

- Monitoring network and organizational systems

- A formal assessment of cyber security risks, undertaken by an employee

- A formal assessment of cyber security risks, undertaken by a parent organization or other external party

- Penetration testing, undertaken by an employee

- Penetration testing, undertaken by a parent organization or other external party

- Assessment of the security of Internet-connected smart devices or Internet of Things (IoT) devices

- Investment in threat intelligence

- Complete audit of IT systems, undertaken by a parent organization or other external party

- Organization conducts other activities to identify cyber security risks

- OR

- Organization does not conduct any activity to identify cyber security risks

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 16

How often does your organization conduct activities to identify cyber security risks? Select all that apply.

- On a scheduled basis

- After a cyber security incident occurs

- When a new IT initiative or project is launched

- On an irregular basis

Cyber security readiness - Question identifier: 17

How often is senior management in your organization given an update on actions taken regarding cyber security? Select all that apply.

- On a scheduled basis

- After a cyber security incident occurs

- When a new IT initiative or project is launched

- Senior management have tools to track cyber security issues

- Senior management is given an update on an irregular basis

- OR

- Senior management is not updated on cyber security issues

Organization resiliency

Organization resiliency – Question identifier: 18

Which three cyber security risks or threats would you consider to have the most detrimental impact on your organization? Select up to three.

- Theft or compromise of software or hardware

- Unauthorized access, manipulation and theft of data

- Identity theft

- Scams and fraud

- Improper usage of computers or network

- Malicious software

- Denial of Service (DoS) or Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS)

- Disruption or defacing of web presence

- Loss of reputation or erosion of public trust

Organization resiliency - Question identifier: 19

How concerned is your organization about its susceptibility to future cyber security risks and threats?

- Extremely concerned

- Very concerned

- Somewhat concerned

- Slightly concerned

- Not at all concerned

Cyber security incidents

Cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 20

To the best of your knowledge, which cyber security incidents impacted your organization in 2022? Select all that apply.

- Incidents to disrupt or deface the business or web presence

- Incidents to steal personal or financial information

- Incidents to steal money or demand ransom payment

- Incidents to steal or manipulate intellectual property or organizational data

- Incidents to access unauthorised or privileged areas

- Incidents to monitor and track organizational activity

- Incidents with an unknown motive

- OR

- Organization was not impacted by any cyber security incidents in 2022

Cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 21

In 2022, was your organization contacted by any of the following parent organizations or other external parties regarding their cyber security events because they may have involved your organization?

Select all that apply.

- Suppliers, customers or partners

- IT consultant or contractor

- Persons or group that perpetrated the incidents

- Cyber risk insurance provider

- Police services

- Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre)

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- Regulator

- Another government organization

- Industry association

- Bank or other financial institution

- Software or service vendor

- Other parties not mentioned above

- OR

- Parent organizations or other external parties did not report cyber security incidents to the organization in 2022

Cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 22

You previously indicated that parent organizations or other external parties contacted your organization about their cyber security events because they may have involved your organization in 2022. How did your organization handle those cyber security events?

Select all that apply.

- Events were resolved internally

- Events were resolved with the parent organization or other external party

- Events were resolved through an IT consultant or contractor

- Events were reported to a police service

- Events were reported to other parents organizations or other external parties

- Organization is currently working with the parent organization or other external party to resolve the events

- OR

- No action was taken by the organization

Cost of cyber security incidents

Cost of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 23

In 2022, what was the total amount your organization spent to prevent or detect cyber security incidents? Exclude costs that were incurred specifically due to previous cyber security incidents (e.g., recovery costs from previous cyber security incidents).

If precise figures are not available, provide your best estimate in Canadian dollars.

Enter "0" if there is no value to report.

- Cost of employee salary related to prevention or detection

- Cost of training employees, suppliers, customers, or partners

- Cost of hiring IT consultants or contractors

- Cost of legal services or public relations (PR) services

- Cost of cyber security software

- Cost of hardware related to cyber security

- Annual cost of cyber risk insurance or equivalent

- Other related costs

Cost of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 24

In 2022, what was the total cost to your organization to recover from the cyber security incidents? Exclude costs related to prevention and detection of cyber security incidents as these were asked in the previous question.

If precise figures are not available, provide your best estimate in Canadian dollars.

Enter "0" if there is no value to report.

- Cost of employee salary related to recovery

- Cost of training employees, suppliers, customers, or partners

- Cost of hiring IT consultants or contractors

- Cost of legal services or public relations (PR) services

- Cost of new or upgraded cyber security software

- Cost of new or upgraded hardware related to cyber security

- Increased cost of cyber risk insurance or equivalent

- Reimbursing suppliers, customers, or partners

- Fines from regulators or authorities

- Ransom payments

- Other related costs

Impact of cyber security incidents

Impact of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 25

To the best of your knowledge, who perpetrated the cyber security incidents in 2022? Select all that apply.

Incidents to disrupt or deface the organization or web presence

Incidents to steal personal or financial information

Incidents to steal money or demand ransom payment

Incidents to steal or manipulate intellectual property or organizational data

Incidents to access unauthorised or privileged areas

Incidents to monitor and track organizational activity

Incidents with an unknown motive

- An employee at a parent organization or other external party

- An internal employee

- Supplier, customer or partner

- OR

- Do not know

Impact of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 26

What were the methods used by the perpetrator for the cyber security incidents? Select all that apply.

Incidents to disrupt or deface the organization or web presence

Incidents to steal personal or financial information

Incidents to steal money or demand ransom payment

Incidents to steal or manipulate intellectual property or organizational data

Incidents to access unauthorised or privileged areas

Incidents to monitor and track organizational activity

Incidents with an unknown motive

- Exploiting software, hardware, or network vulnerabilities

- Hacking or password cracking

- Identity theft

- Scams and fraud

- Ransomware

- Other malicious software

- Denial of Service (DoS) or Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS)

- Disruption or defacing of web presence

- Abuse of access privileges by a current or former internal party

- Other

- OR

- Do not know

Impact of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 27

You previously indicated that your organization has cyber risk insurance. Did your organization attempt to make a claim on that policy after the cyber security incidents in 2022? Select all that apply.

- Yes, we successfully made a claim against the organization's cyber risk insurance

- Yes, we attempted to make a claim against the organization's cyber risk insurance but were unsuccessful

- Yes, we attempted to make a claim against the organization's cyber risk insurance and it is still in progress

- OR

- No, we have not attempted to make a claim for any of the cyber security incidents

Impact of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 28

How was your organization impacted by the cyber security incidents in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Loss of revenue

- Loss of suppliers, customers, or partners

- Additional repair or recovery costs

- Prevented the use of resources or services

- Prevented employees from carrying out their day-to-day work

- Additional time required by employees to complete their day-to-day work

- Damage to the reputation of the organization or erosion of public trust

- Fines from regulators or authorities

- Discouraged organization from carrying out a future activity that was planned

- Minor incidents, impact was minimal to the organization

- Other

- OR

- Do not know

Impact of cyber security incidents - Question identifier: 29

As a result of cyber security incidents, approximately how many hours of downtime did your organization experience in 2022?

Include:

- total downtime for mobile devices, desktops and networks

- time periods during which there was either reduced activity or inactivity of employees or the organization.

If precise figures are not available, provide your best estimate.

- Hours

- OR

- Organization did not experience any downtime in 2022

- OR

- Do not know

Cyber security incidents reporting

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 30

Did your organization report any cyber security incidents to a police service in 2022?

Include all levels of police service including federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Indigenous.

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 31

Which cyber security incidents did your organization report to a police service in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Incidents to disrupt or deface the organization or web presence

- Incidents to steal personal or financial information

- Incidents to steal money or demand ransom payment

- Incidents to steal or manipulate intellectual property or organizational data

- Incidents to access unauthorised or privileged areas

- Incidents to monitor and track organizational activity

- Incidents with an unknown motive

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 32

What were the reasons for reporting incidents to a police service in 2022? Select all that apply.

- To reduce the damage caused by the incidents

- To lower the probability of other organizations being impacted by the same incidents

- To help catch the perpetrators

- To fulfill the requirements of customers, suppliers, partners, regulators, cyber security standards or cyber security certification programs

- Other

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 33

What were the reasons for not reporting some or all of the cyber security incidents to a police service in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Incidents were resolved internally

- Incidents were resolved through an IT consultant or contractor

- To protect the reputation of the organization or stakeholders

- Did not want to spend more time or money on the issue

- Police service would not consider incidents important enough

- Police service was unsatisfactory in the past

- Unsure of where or how to report

- Reporting process is too complicated

- Did not think the perpetrator would be convicted or adequately punished

- Minor incidents, not important enough for organization

- Lack of evidence

- Did not think of contacting a police service

- OR

- Organization reported all cyber security incidents to a police service in 2022

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 34

Excluding police services, which parent organization or other external party did your organization report the cyber security incidents to in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Suppliers, customers or partners

- IT consultant or contractor

- Cyber risk insurance provider

- Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre)

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC)

- Other government department or agency

- Regulator

- Industry association

- Bank or other financial institution

- Software or service vendor

- OR

- Organization did not report any cyber security incidents to a parent organization or other external parties in 2022

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 35

What were the reasons for not reporting some or all the of the cyber security incidents to a parent organization or other external party in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Incidents were reported to a police service only

- Incidents were resolved internally

- To keep knowledge of the incidents internal

- To protect the reputation of the organization or stakeholders

- Lack of evidence

- No benefit to reporting

- Minor incidents, not important enough for organization

- Did not think of reporting the incidents to a parent organization or other external party

- OR

- Organization reported all cyber security incidents to a parent organization or other external parties in 2022

Cyber security incidents reporting - Question identifier: 36

In responding to the cyber security incidents in 2022, which parent organizations or external parties did your organization contact for information or advice?

Select all that apply.

- Suppliers, customers or partners

- IT consultant or contractor

- Cyber risk insurance provider

- Legal services

- Police services

- Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre)

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC)

- Other Government department or agency

- Regulator

- Industry association

- Bank or other financial institution

- Software or service vendor

- Internet community

- Family, friends, or acquaintances

- Computer repair shop

- OR

- Organization did not contact any parent organizations or external parties in 2022

Notification of intent to extract web data

Notification of intent to extract web data - Question identifier: 37

What is this organization's website address?

We may also visit this organization's website to search for additional publicly available information using automated methods, being careful not to impede the functionality of the website.

Current cyber security trends

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 38

In 2022, what was the total value of ransom payments made by your organization?

- More than $0, but less than or equal to $10,000

- More than $10,000, but less than or equal to $50,000

- More than $50,000, but less than or equal to $100,000

- More than $100,000, but less than or equal to $250,000

- More than $250,000, but less than or equal to $500,000

- More than $500,000

- The organization did not make ransom payments in 2022

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 39

In 2022, did your organization make ransom payments using cryptocurrency?

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 40

In 2022, which parent organizations or external parties did your organization work with to resolve ransomware incidents?

Include all parent organizations or external parties your organization reported the ransomware incident to.

Select all that apply.

- IT consultant or contractor

- Cyber risk insurance provider

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP)

- Other police services

- Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre)

- Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre (CAFC)

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- Other parent organizations or external parties

- OR

- The organization did not work with parent organizations or external parties to resolve ransomware incidents in 2022

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 41

Why does your organization not have cyber risk insurance?

Select all that apply.

- The organization's existing insurance policies cover cyber security risks

- The cost of cyber risk insurance is too high

- The organization's existing cyber security measures provide enough protection that cyber risk insurance is unnecessary

- The organization had no cyber security risks

- The organization has not considered obtaining cyber risk insurance

- Not applicable to this organization

- Other reasons for not having cyber risk insurance

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 42

Which of the following population groups do your organization's cyber security employees belong to?

Select all that apply.

- White

- Indigenous

- Visible minority

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 43

What are the highest academic certificates, diplomas or degrees your organization's cyber security employees hold?

Select the highest academic certificate, diploma or degree that each cyber security employee holds.

- Less than high school diploma or its equivalent

- High school diploma or a high school equivalency certificate

- Trades certificate or diploma

- College, CEGEP or other non-university certificate or diploma (other than trades certificates or diplomas)

- University certificate or diploma below the bachelor's level

- Bachelor's degree

- University certificate, diploma or degree above the bachelor's level

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends - Question identifier: 44

What cyber security certifications do your organization's cyber security employees hold?

Include certifications that are no longer active.

Exclude academic certificates, diplomas or degrees.

Select all that apply.

- Certified Ethical Hacker

- Certified Information Security Manager

- Certified Information Systems Professional

- GIAC Security Expert

- Security+

- Other certifications

- OR

- None

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends – Question identifier: 45

Which qualification does your organization value the most when evaluating a potential new cyber security employee?

- Experience working in cyber security

- Academic certificates, diplomas or degrees related to cyber security

- Cyber security certifications

- Other cyber security training

- Other qualifications

- Specify other qualifications (text box)

- Organization has never attempted to hire a cyber security employee

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends – Question identifier: 46

In 2022, did your organization encounter any challenges finding qualified cyber security employees or retaining existing cyber security employees?

Select all that apply.

- Challenges finding qualified cyber security employees

- Challenges retaining cyber security employees

- OR

- The organization did not encounter any challenges finding or retaining qualified cyber security employees in 2022

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends – Question identifier: 47

What challenges did your organization encounter when hiring cyber security employees in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Applicants lacking skills

- Applicants lacking experience

- Salary requests too high

- Not enough time or resources for effective recruitment

- Lack of candidate interest in the position

- Other challenges

- Specify other challenges (text box)

- OR

- Do not know

Current cyber security trends – Question identifier: 48

For which reasons did cyber security employees leave your organization in 2022?

Select all that apply.

- Recruited by other organization

- Limited internal promotion or development opportunities

- High stress levels at work

- Lack of flexibility (work-life balance)

- Better salary

- Other reasons

- Specify other reasons (text box)

- OR

- No cyber security employees left the organization in 2022

- OR

- Do not know