Correction notice

Date: May 7, 2024

Errors were found in the graphs on this page. The data were correct and only the visuals were incorrect.

Jenneke Le Moullec, Chief, Longitudinal Social Data Development Program

Charles Uwitwongeye, Survey Manager, Centre for Social Data Integration and Development

James Falconer, Chief, Census Futures

Sonia Bataebo, Account Executive, Centre for Social Data Integration and Development

Abstract

This report presents the findings from the deliberative public engagement research project conducted by Statistics Canada from October to December 2022. The qualitative research study explores the social acceptability surrounding the use of person-based linked administrative dataFootnote 1 in statistical programs. A total of 45 participants were recruited, and each participated in 10 sessions in either English or French. During these sessions, participants were informed on the topic, brainstormed, deliberated, and finally voted on a set of final statements. This report presents summaries of the findings in terms of overall themes, representative quotes from session participants, and the results of short participant surveys.

While the aim overall was to understand the conditions under which the Canadian public finds the use of linked social (person-based) administrative data acceptable and the guiding principles on the use of such data for statistical insights, we heard that this research question must be answered within the greater context of Statistics Canada's mandate, privacy and confidentiality, data impact, and public awareness.

The research is intended to illuminate why individuals hold particular views on the use of data for statistical insights. Guided by the deliberative research design process, the informed views of the 45 participants culminated in a set of 14 final overarching statements. These statements, which are non-binding, are an artifact of the research process and should not be taken out of context.

Methodology

This project is a qualitative study that employed a deliberative public engagement research framework. Deliberative research is a qualitative technique increasingly used within the social sciences and is distinguished from other forms of qualitative research in two ways: (1) participants are provided appropriate information on which they base their opinions, allowing them to provide meaningful input, and (2) a set of final statements are developed by the participants and voted on according to the premise that, like in real social and political life, members of society may have differences in values, opinions, and interests, yet they need to strive for common rules and practices that all can live with.

The steps undertaken in this research process were as follows:

Phase 1: Participant recruitment

Phase 2: Introductions and information sharing

Phase 3: Brainstorming

Phase 4: Deliberations on identified topics

Phase 5: Statement review

Phase 6: Final statement voting

Phase 7: Closeout and evaluation

Participant recruitment emphasized diversity more than strict representativeness. Because the results of deliberative research are not intended to be generalized to the overall population, our recruitment of participants instead maximized the diversity of opinions and perspectives by age, gender, region, and racialized and Indigenous status. Two concurrent deliberative panels were conducted in English and French over the course of 10 weekly sessions from October to December 2022. The constraints of the deliberative sessions meant that bilingual sessions with simultaneous interpretation were impracticable, so the research design opted for separate, concurrent sessions in each language, with the deliberative statements emerging from each group synthesized afterward by the moderator.

How deliberative statements were formed

A common technique used in deliberative research is to explore the topic, listen to the underlying principles of what is being said, and have the participants develop the statements facilitated by the moderator. The guiding statements are not limited to addressing gaps in what Statistics Canada currently does. That is, while some statements may be aspirational, others point to activities already undertaken at Statistics Canada.

- Listen: The researchers listened to the brainstorming and deliberative discussions.

- Summarize: The underlying principles from the brainstorming and deliberative discussions were summarized into a total of nine bilingual statements.

- Propose statements: These nine statements were shared with participants in advance of the discussion.

- Discuss: The nine statements were assessed one by one by participants in group sessions. Participants suggested changes to statement wording (English and French), question intent, omissions, and proposed additional statements.

- Finalize: Feedback on the nine statements was incorporated into final bilingual versions. The number of statements grew from nine to fourteen.

- Vote: Participants voted on their level of agreement with each of the fourteen statements. Participants were given the opportunity to discuss and criticize the final statements, though no further changes were made.

Final statements and voting

Table 1 shows that the final deliberative statements achieved a high level of consensus among group participants.

| Statements | English (N = 24) | French (N = 21) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | D | SD | SA | A | N | D | SD | |

| As the national statistical agency, Statistics Canada maintains an essential role in providing quality information to inform decision making in Canada. | 71% | 25% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 62% | 33% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| Statistics Canada is an important source of high quality and credible information. | 79% | 21% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 71% | 29% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Statistics Canada is an important source of high quality and credible information. | 33% | 58% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 57% | 38% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| The following are all appropriate ways for Statistics Canada to fulfill its role: (1) collecting information from surveys, (2) collecting administrative data from public and private organizations, and (3) linking across survey and administrative data. | 38% | 54% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 38% | 57% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| When considering its role of providing quality information to inform decision making, Statistics Canada must be held accountable to a very high standard in terms of data quality. | 88% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 90% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| To improve well-being in Canada, Statistics Canada data should be used effectively by decision makers. | 75% | 25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 67% | 24% | 10% | 0% | 0% |

| Statistics Canada data should have an impact on improving well-being in Canada, but unfortunately, sometimes this impact is not visible. | 50% | 38% | 8% | 4% | 0% | 48% | 33% | 19% | 0% | 0% |

| The public needs to hear where, why, when and how data are used to have a measurable and positive impact. | 42% | 46% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 67% | 29% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| To ensure the continued support of the public and to enhance its reputation, Statistics Canada should proactively communicate its impartiality. | 54% | 29% | 17% | 0% | 0% | 67% | 33% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| It is important that Statistics Canada produce data that highlights the experiences of specific population groups, especially those who experience disadvantage. | 63% | 21% | 17% | 0% | 0% | 38% | 48% | 10% | 5% | 0% |

| Statistics Canada should actively communicate information about the data releases and analytical publications to the public using a variety of strategies and platforms. | 58% | 38% | 0% | 4% | 0% | 57% | 38% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| When considering the amount of information it holds, Statistics Canada must be held accountable to a very high standard in terms of privacy protection. | 88% | 13% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| It is important that Statistics Canada data are protected from any use that is not for the public good. This includes threats of misuse which are (1) internal to Statistics Canada, (2) within the rest of government and (3) external to government, now and in the future. | 71% | 29% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 81% | 19% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Statistics Canada should have sound measures and accountabilities in place for (1) collecting data and linking data, (2) protecting data, (3) disclosing data, (4) retaining and destroying data, and (5) managing privacy breaches. These measures may need to evolve over time. These measures should also be actively and well communicated to individuals, agents of parliament and parliament itself. | 75% | 21% | 0% | 4% | 0% | 81% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% |

| Table key: SA = strongly agree, A = agree, N = neither agree nor disagree, D = disagree, SD = strongly disagree | ||||||||||

Findings

Four major themes were identified: (1) the use of linked administrative data, (2) privacy and confidentiality, (3) social data impact, and (4) public awareness.

Theme 1: The use of linked administrative data

The use of administrative data was accepted, but with consideration for the volume and types of data.

The vast majority of participants accepted the use of linked administrative data in statistical programs, and many participants expected such use. When hearing about when, why, and how Statistics Canada used linked administrative data in statistical programs, many participants either already knew, expected, or were unsurprised to learn of such uses and did not express concerns. A few participants were not enthusiastic about the data held by Statistics Canada but viewed these holdings as necessary and that the current approach was better than other alternatives. The functions of a national statistical agency in Canada were viewed as imperative, even among those who preferred their data not to be included.

"I don't really have any issues when it comes to the use of administrative data. I think with the anonymity of it all and the way it's collected and as well as knowing that it's kept in a really safe place with no risk of data breaches, it's not really a big concern for me."

Male, aged 31 to 40, Atlantic

"I hear what the concerns are—collecting data and connecting it to government. But there seems to be agreement in the group here that it is important to collect all this data. How would you propose to collect this data and somehow not have it connected to government? What is the other option?"

Male, aged 71 or older, Prairies

Participants generally understood Statistics Canada's role in providing statistical insights through surveys and administrative data and supported it; this included those concerned about Statistics Canada's survey and administrative data holdings. Some participants were concerned with the quality of administrative data and its fitness for use in statistical programs. Participants recognized the varying degree of control that Statistics Canada has over different data sources, with the greatest control over surveys and less control over administrative data collected by other organizations. Some participants expressed concern for the quality of administrative data, over which they acknowledge Statistics Canada has less control.

"I don't know why, but I fear that there are more data errors coming from companies in the private sector. I am concerned that there are errors in the transmission of data to Statistics Canada. That is an impression I have."

Female, aged 31 to 40, Ontario

When considering the types of administrative data held by Statistics Canada, some participants drew distinctions from where Statistics Canada received the data. It was explained to participants that, under the authority of the Statistics Act, Statistics Canada receives administrative data from different types of organizations, including public and private organizations. Participants understood that sharing these data went through a thorough review and justification process and that this was reported publicly on the Statistics Canada website. While participants accepted and supported this, a few continued drawing distinctions on where the data was received from.

The potential for administrative data biases was important to participants, and participants noted that inherent biases might come with data collected through administrative systems. Examples of these biases included those stemming from traditional Western perspectives, which may not accurately reflect diversity in Canada.

Most participants accepted the reception, use, and storage of personal identifiers such as first and last names. Participants understood that personal identifiers such as first and last names were sometimes required for record linkage and were, therefore, sometimes included on administrative data files from other organizations. It was explained to participants how these identifiers were used and how they were stored apart from analytical files and not disclosed. While a few participants expressed concern about the volume and type of data Statistics Canada holds, concerns were not specifically directed to the receipt of personal identifiers or the nature of the linkage activities Statistics Canada carries out.

Participants recognized that much information about an individual could be brought together through record linkage. However, participants did not express the need to define a specific limit for record linkage activities. Participants considered record linkage a statistical technique and, while recognizing it as privacy-invasive, did not specifically suggest limits on its use provided it was being used in statistical programs. While most participants accepted Statistics Canada's use of linked administrative data, a few expressed discomfort. If given the option, some participants preferred responding to surveys directly, while others preferred their administrative data being used instead.

"In one of the presentations, it was brought up that administrative data reduces response burden, and I think that is a good thing. I don't like filling out long surveys, so if Statistics Canada can get the information through another way, then go for it."

Female, aged 31 to 40, Quebec

"I prefer to fill out the questionnaire, actually."

Male, aged 51 to 60, Atlantic

Theme 2: privacy and confidentiality

Participants hold Statistics Canada to a high standard of accountability, but trust Statistics Canada to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their personal information.

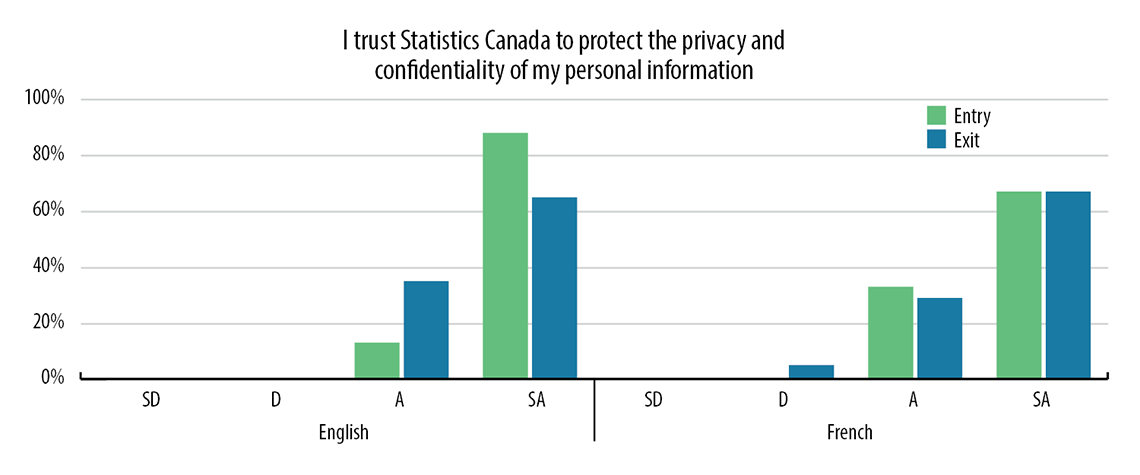

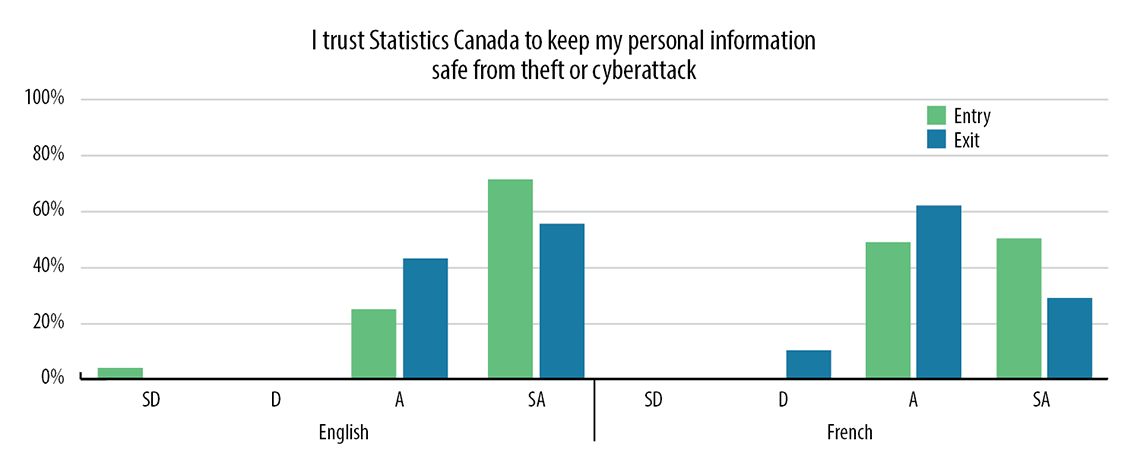

At the beginning of the DPER project, participants were asked in the entry survey whether they trusted Statistics Canada to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their personal information and whether they trusted Statistics Canada to protect their personal information from cyberattacks. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, at the beginning of the DPER, participants had a high level of trust in this respect.

Throughout the DPER, participants became increasingly knowledgeable on the types, volumes, and nature of administrative data held by Statistics Canada, including data on sensitive topics and personal identifiers. Participants also become aware of the risks associated with cyberattacks and data breaches, resulting in a slight downward shift in the responses to the trust questions when measured in the exit survey. Despite this increased knowledge, participants continued trusting Statistics Canada to protect their personal information.See Table 2 and Table 3 below.

| I trust Statistics Canada to protect the privacy and confidentiality of my personal information | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | French | |||||||

| SD | D | A | SA | SD | D | A | SA | |

| Entry | 0% | 0% | 13% | 88% | 0% | 0% | 33% | 67% |

| Exit | 0% | 0% | 35% | 65% | 0% | 5% | 29% | 67% |

| Table key: SD = strongly disagree, D = somewhat disagree, A = somewhat agree, SA = strongly agree | ||||||||

| I trust Statistics Canada to keep my personal information safe from theft or cyberattack | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | French | |||||||

| SD | D | A | SA | SD | D | A | SA | |

| Entry | 4% | 0% | 25% | 71% | 0% | 0% | 50% | 50% |

| Exit | 0% | 0% | 43% | 57% | 0% | 10% | 62% | 29% |

| Table key: SD = strongly disagree, D = somewhat disagree, A = somewhat agree, SA = strongly agree | ||||||||

Regarding privacy management, participants expected Statistics Canada to be held to an equal or higher standard than other organizations. While all participants believed it was of utmost importance for Statistics Canada to protect privacy, there was no agreement as to whether Statistics Canada should be held to the same standard, or a higher standard, as other organizations.

"I would hold Statistics Canada to the same level of expectation that I would hold any public body that has been granted custodianship of any individual's personal data. I don't think Statistics Canada should be held to a specifically higher level because of the volume or type or breadth of data that it contains, and it certainly should not be held to a lower level."

Male, aged 31 to 40, Atlantic

Participants wanted to know what measures and frameworks were in place to protect their data. Participants were informed on a range of measures Statistics Canada uses to protect data, including legislative authorities and obligations, employee responsibilities, and technical details such as data anonymization. Participants were generally interested in understanding these measures, did not express specific concerns and generally seemed satisfied.

Despite being comfortable with the privacy protection safeguards, some participants remained concerned about the potential misuse of personal data, presently and in the future. Participants expressed varying degrees of concern related to the potential misuse of personal data. While most participants did not dispute that data misuse was theoretically possible, many participants did not focus on the risk of misuse. Those who did express concern raised different reasons. Some participants cited the risk of partisan use of data in the future, while other participants were concerned with bad actors or identity theft. Participants recognized the possibility of a data breach, the harm this could have on individuals, and the importance of breaches being properly managed.

"I'm concerned with the connection, even though you said that Statistics Canada works at arm's length from the government. Yeah, that bothers me. Any government of the time—the former, the current, the next—how are they going to use our data? How they are going to manipulate our data and take advantage of our data, that concerns me. My biggest concern is the connection between Statistics Canada and the government and that they invade our private lives."

Female, aged 41 to 50, Ontario

"A data breach is one thing when you consider the fact admin data has everything from your social insurance, your healthcare number, your address, your name, your babies, your everything. They have access to anything and everything and we give them more when they ask."

Female, aged 61 to 70, Prairies

Given the inherently privacy-invasive nature of data linkage, along with the mandatory collection of some survey and administrative information, and the inability for individuals to opt out or give informed consent, Statistics Canada should understand Canadians' perspectives toward its important obligation to protect the privacy and confidentiality of individuals' data.

Theme 3: social data impact

Participants trust that Statistics Canada will use their data for the public good but want to see more evidence that their data have a positive real-world impact.

Beyond how data are collected and stored, participants focused on what data are used for and the social impact this has. The social contract surrounding the use of personal data by Statistics Canada is predicated on the data being used responsibly for the public good. That is, to improve the lives of those living in Canada. However, beyond trusting that Statistics Canada will keep their data safe, participants want to trust that how Statistics Canada is using their data will improve the lives of those in Canada.

"I agree that any data should be used for whatever it is meant to be [by Statistics Canada]. But I still have my concerns about how it's stored and how it is used now more than ever."

Female, aged 41 to 50, Ontario

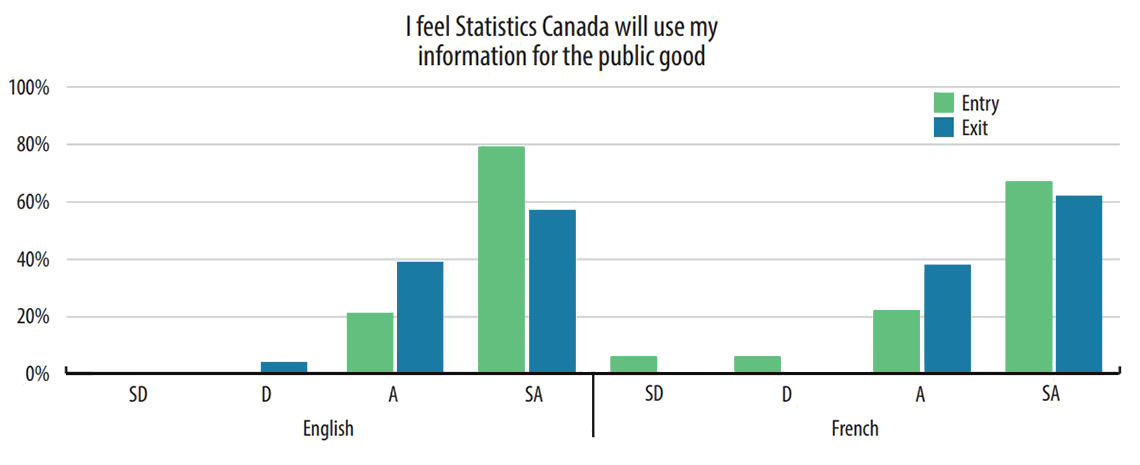

At the beginning of the DPER project, participants were asked in the entry survey if they felt Statistics Canada used their data for the public good. As shown in Table 4, at the beginning of the DPER, most participants felt strongly that this was the case.

Throughout the DPER process, participants increasingly considered the types of social insights Statistics Canada could produce, including the status of water quality in Indigenous communities, child maltreatment, housing conditions, and the association between environmental exposure and health outcomes. With this consideration, participants increasingly found "using data for the public good" to be challenging to define, as there are multiple and competing priorities.

At the end of the DPER, as shown in the exit survey responses in Table 4, participants felt that Statistics Canada used their information for the public good. However, fewer participants strongly agreed this was the case. This shift can be explained by the deeper consideration participants gave to the concept of public good throughout the DPER process.

| I feel Statistics Canada will use my information for the public good | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | French | |||||||

| SD | D | A | SA | SD | D | A | SA | |

| Entry | 0% | 0% | 21% | 79% | 6% | 6% | 22% | 67% |

| Exit | 0% | 4% | 39% | 57% | 0% | 0% | 38% | 62% |

| Table key: SD = strongly disagree, D = somewhat disagree, A = somewhat agree, SA = strongly agree | ||||||||

Participants wanted to know how research priorities were set at Statistics Canada, including the role of the rest of the government in setting these priorities and how funding was allocated. When discussing how their data were being used, participants were keen to understand the larger context of how research priorities were set.

The importance of social data impact on minority and equity-seeking groups or people was underscored by some participants. Indigenous data topics were discussed throughout the sessions. These discussions were informed by presentations from Statistics Canada's Centre for Indigenous Statistics and Partnerships and an Indigenous data expert external to Statistics Canada. Some participants raised the apparent invisibility of the impact that studies on Indigenous topics have had. Some participants also mentioned the high importance of social data impact for minority and equity-seeking groups, such as linguistic minorities, people with disabilities and gender-diverse groups.

Participants were generally less focused on which data were collected, linked, and analyzed from a privacy perspective, if safeguards are in place. Instead, they were more concerned with the "right" things being studied and that these studies led to change. When asking participants about their impressions on the types of data held by Statistics Canada and the linkage activities that were undertaken, participants persistently connected this discussion not only to the research question their data would be used to answer but also to the impact the research study would have.

"I had some time this week to look around on the Statistics Canada website and was looking specifically at Indigenous people. The first statistic on Indigenous people is homicide trends in Canada. Then another one is Indigenous people and income and women's full-time employment. Then housing conditions among First Nations and Inuit, and Indigenous shelters for victims of abuse. These stats are pretty negative if you ask me. So, I just think: Why are we collecting this data if nothing is changing, if nothing is happening?"

Female, aged 61 to 70, Prairies

Participants held different opinions on the degree to which Statistics Canada should influence government policy. Participants were divided as to the role Statistics Canada should play in terms of setting research priorities and the influence the research findings should have in shaping policy and program decisions by the government. For example, one participant suggested that Statistics Canada should have a role in identifying important social issues, while another participant believed that Statistics Canada should operate autonomously from the rest of the government.

Participants viewed Statistics Canada as important in providing quality information, particularly in an environment where misinformation and disinformation exist. Some participants distinguished between statistical information provided by Statistics Canada compared with other private and non-profit organizations that provide statistical information. Statistics Canada was viewed as holding a stronger reputation for higher quality information. Some participants also mentioned that Statistics Canada played an important role in fighting against misinformation and disinformation.

"I am really quite concerned about misinformation today and where people are getting their information from. Has Statistics Canada been talking about how to keep a good reputation?"

Female, aged 61 to 70, Prairies

Theme 4: public awareness

Participants want to hear more from Statistics Canada: What data do we have? How are we collecting, storing, and analyzing data? What interesting research findings have we discovered?

Participants stressed the importance of public awareness through active and transparent communications. Most participants believed that Statistics Canada should be transparent and actively communicate information about its data holdings and how it uses personal information.

Early in the research process, a few participants raised the topics of active consent and mandatory disclosure statements in the context of Statistics Canada's use of administrative data. Throughout the sessions, participants learned that Statistics Canada does not generally seek consent for using administrative data, nor does it include mandatory disclosure statements on the data collected by another organization and brought into Statistics Canada.

"It's important that the information that is being requested is used only for the purposes that it's being requested for and not shared in any other way so that I fully know what information I'm giving, where it's going, how it's going to be used."

Male, aged 71 or older, Prairies

After learning this, participants did not suggest implementing active consent or mandatory statements. Instead, they stressed the importance of transparency and actively communicating information about data holdings and the use of personal information. Beyond making such information available on the website, many participants felt Statistics Canada should try to actively communicate this information to those living in Canada.

Most participants believed that Statistics Canada should be transparent and actively communicate information about how their data are protected, including information about data breaches. While participants generally agreed that information on data breaches should be actively communicated, some participants mentioned that this communication should not be limited to those directly affected by a breach but should be communicated more broadly, for example, through the media. Additionally, before becoming informed about this research, some participants believed they would only find out if they had been a victim of a data breach through the media and did not know that Statistics Canada would contact them directly.

Most participants believed that Statistics Canada should be transparent and actively communicate information about analytical products and research studies. Participants became more aware of Statistics Canada's analytical products throughout the research process. Many participants became more interested in these, visiting the Statistics Canada website to read and learn more about various subjects. Many participants expressed that the information produced by Statistics Canada is interesting, relevant, and useful to Canadians and that the information should be actively communicated so that it can be well leveraged. Some participants suggested communication channels that may be effective for Statistics Canada, including traditional media, social media, and other platforms such as podcasts.

Limitations

Limited information and perspectives from outside Statistics Canada were shared with participants. The evaluation survey results suggest that participants believed the information provided was unbiased and comprehensive; however, it is recognized that the inclusion of different information may have impacted the study results.

While the research included topics related to minority and equity-seeking groups, this was not the main research question. As such, further studies should be carried out to address the unique circumstances of different subpopulations, including distinctions-based Indigenous groups.

Discussion

The use of linked administrative data must be situated within the greater context of Statistics Canada's mandate, authorities, and obligations. Participants did not separate guiding principles on the use of linked administrative data from the activities of Statistics Canada overall.

While the objective of this research was to listen to deliberations on the use of linked administrative data in statistical programs, the discussions repeatedly gravitated away from the core topic towards the greater context of the role and activities of the national statistical agency.

Statistics Canada organizes its legal framework, policies and directives, data governance, and business processes around managing different classifications of data, such as survey data, administrative data, and identified and de-identified data. Participants, however, did not necessarily delineate different types of data in this way and were focused instead on the role and mandate of Statistics Canada, privacy and confidentiality, data impact, and public awareness.

Because of this perspective, discussions on the boundaries of social acceptability did not focus specifically on the conditions under which administrative data linkages were acceptable. However, the boundaries of social acceptability and the conditions under which administrative data linkage is acceptable can be inferred from the other key findings and themes, such as privacy and confidentiality, using data for the public good, and transparency.

Even after being made knowledgeable of the volume, types, nature, and purposes of linkage activities at Statistics Canada, including details on the Social Data Linkage Environment and the use of administrative data in programs like the Census of Population and the Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohorts, participants did not narrow the discussions or deliberative statements to the conditions under which data linkage was appropriate.

Participants were recruited from different demographic profiles and backgrounds with varying levels of trust in government and public institutions. While the overarching aim of the DPER was to understand the conditions under which the diverse Canadian public finds the use of linked administrative data acceptable and the guiding principles on the use of data for statistical insights, it was both expected and confirmed that participants would not fully converge and that some minority views would sustain. Most participants upheld the deliberative statements, providing insights into guiding principles. However, it is essential to recall that underlying the statements and their support rests diverging views that highlight the diversity of views in Canada.

This research not only informs the conditions under which Canadians find the use of person-based linked administrative data socially acceptable but helps highlight that the use of administrative data must be situated within the greater context of the role and activities of the national statistical agency.

Conclusion

Statistics Canada enjoys an extraordinarily high level of public goodwill, evidenced by Canada's world-leading response rate to the census; the high regard with which Statistics Canada is held as an agency domestically and globally; and the authoritative position of its data for use in academic research, public policy, and in the national conversation on social, economic, and environmental issues. Canadians are invested in the reputation of Statistics Canada and are willing to give up some of their time, trust, and privacy to ensure the quality of the data making up the diverse portrait of our country. Statistics Canada can capitalize on its trust relationship with Canadians to enhance its statistical programs, without depleting its supply of trust, as long as it can maintain and enhance its trust-building activities and demonstrate the use of Canadians' data for the public good.

We learned that our research participants don't necessarily perceive a boundary or limit on the use of linked administrative data for statistical programs. As long as high-quality data are being analyzed in a protected environment and the necessity and proportionality of the data can be justified to the public, participants generally accept that microdata linkages can and should be used to produce powerful new insights. This evidence suggests that Statistics Canada can consider being bolder in its vision for an integrated statistical infrastructure if the corresponding transparency and accountability measures are clearly communicated and demonstrated to the public.

The questions and insights from participants should provoke a careful introspection about how Statistics Canada should shape its "identity" as an agency vis-à-vis the public and the government. For example, can Statistics Canada retain scientific rigour and credibility while responding to the evolving data needs of society? Is disseminating truthful information where its obligation ends, or must Statistics Canada wage public battle against misinformation? The value of such questions becomes realized when we acknowledge the gaps between what the public expects from Statistics Canada and what we can hope to accomplish. We must continue the dialogue with Canadians as we define ourselves as an agency.

Several recommendations emerged from the DPER sessions that, if adopted, will meaningfully contribute to Statistics Canada's trust relationship with the Canadian public. Some recommendations were explicitly suggested by participants, while others were proposed by the project team in response to participants' stated needs and desires. First, participants suggested taking ongoing measures about public trust in Statistics Canada and other data issues. Statistics Canada should consider longitudinal public opinion research to keep a pulse on the perspectives in the general population. Nearly all DPER participants would be willing to join a citizen advisory panel that Statistics Canada can use for brainstorming and pilot testing public opinion questions. Second, participants value open and transparent communication about how Statistics Canada is using data. Statistics Canada should consider proactively using external communications channels in traditional and digital media and optimize the use of the Trust Centre for transparency, accountability, and responsive communication. Third, participants want to see the impact of their data. Statistics Canada should innovate a new type of assessment tool that, to our knowledge, has not yet been considered: a "data impact assessment" should evaluate whether, and how, data products are being used to effect real-world change. As Statistics Canada continues to increase the use of administrative data in statistical programs, the result could be fewer and fewer direct interactions with the public upon which a trust basis can be built. Implementing these recommendations would open new avenues for direct public interaction and trust building on which the quality of our data depends.

One of the major strengths of this research method, and of this project in particular, was our privileged access to insights from regular Canadians. It's humbling to discover that most Canadians don't give Statistics Canada a moment's thought during the course of their daily lives. But when Canadians are brought together in a discussion forum, educated about what we do, and compelled to decide about what they think, it generates a wealth of qualitative data that we can use to course correct the direction of our agency, its statistical programs, and its public communication. This research method should be adopted as a recurring study to further investigate bigger and deeper issues facing Statistics Canada's future.